Federal Buildings Use Far More Energy Than They Should. This Bipartisan Bill Would Help Cut the Waste.

Let's Save Energy

Alliance to Save Energy's Blog

The U.S. government spends roughly $6 billion each year on the energy consumed by people and systems within federal buildings. This cost is far higher than necessary because many older federal buildings are very energy inefficient and do not take advantage of new technologies that can shift, shape and integrate energy needs with innovative solutions. Ultimately, it is the taxpayer who bears this burden of paying for the wasted energy and water demanded by those poorly-performing buildings—that’s money spent on utility bills that could be better spent elsewhere.

Upgrading the equipment and systems in existing buildings would be an investment bargain that saves money for decades, but it’s not happening nearly as much as it should. That’s in part because federal law discourages the building managers who decide on potential upgrades from implementing some types of projects that would improve energy efficiency and increase resilience and sustainability. But a proposal pending in both chambers of Congress, the All-of-the-Above Federal Building Energy Conservation Act, would help fix those policy roadblocks—and could spur a wave of improvements in efficiency, resilience and energy security that would save taxpayers big money.

New Federal Buildings Are Generally Energy Efficient, but Many Older Ones are Ripe for Improvement

When a federal building is inefficient, generations of taxpayers are saddled with higher energy costs over the lifetime of that building. Fortunately, federal law recognizes this by requiring all new buildings to exceed (by 30 percent or more) the most recent building codes and standards, if identified as cost-effective. Nearly 94 percent of federal buildings built since 2007 have met this requirement.

"Globally, one-third of the world's energy is consumed by buildings, but most buildings are deeply inefficient. Just implementing today's best practices could cut global energy demand by one-third by 2050. … Improving the energy efficiency of buildings is a fast, cost-effective way to manage carbon pollution, spur economic development and enhance local air quality." -

Jennifer Layke, World Resources Institute

Unfortunately, there is no similar measure for existing buildings. While the increasing efficiency underpinning new buildings through codes and industry standards is a good thing, national laboratory modeling reveals the best bang for the buck lies in retrofitting our existing buildings. By adding similar energy performance requirements to renovations as exist for new construction, it would shift the focus of energy upgrades from piecemeal equipment replacement (widgets) to deep energy retrofits (including building envelope and systems).

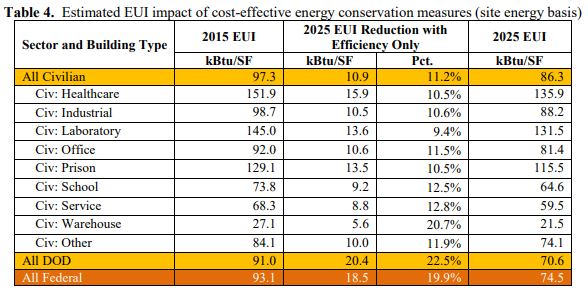

In 2014 the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) reported that existing federal buildings could realize an energy use intensity (EUI) reduction of nearly 20 percent by 2025 (from a 2015 baseline), compared to just a 2.7 percent reduction likely to be realized by the next generation of replacement buildings. (See Table 1.) This represents by far the best opportunity to capture the energy waste reductions necessary to not only realize short-term benefits such as decreased costs, improved performance and comfort, and increased resilience, energy security and economic opportunity; but also to meet long-term sustainability goals.

(Source: PNNL)

Current Law Presents Obstacles to Improving Existing Federal Buildings

There are a lot of neat things we can do with buildings to make the grid more resilient and sustainable—but we must achieve efficiency first. Today, we have the knowledge, equipment and financing options to address waste while improving performance and connectivity within existing federal buildings, but policy barriers to investment still exist.

“Deep decarbonization” scenarios rely on pervasive electrification of end-uses such as space and water heating in buildings, while simultaneously “greening” the grid through increased efficiency and carbon-free generation. However, under federal law, “major retrofits” of greater than $2.5 million trigger an incremental ban on fossil-derived energy consumed in those buildings, including electricity. While this unworkable requirement has yet to be implemented, it would sideline investments in highly-efficient but fossil-fuel-dependent innovations like combined heat and power (CHP).

Energy savings are not the only improvements available to older buildings. The speed at which building science and technologies advance outpaces federal efforts to capture unprecedented opportunities for grid integration. Harnessing these advancements would allow inefficient buildings of yesterday to outperform their cousins of tomorrow in many ways. Systems efficiency and grid connectivity enable demand-side options that increase the resilience of the electricity grid, such as smart electric vehicle charging, energy and thermal storage, peak load shifting through demand response, the provision of grid-essential ancillary services, and distributed renewables generation. Each of these capabilities can reduce emissions and reduce strains on the grid only if implemented; they do no good sitting on the shelf.

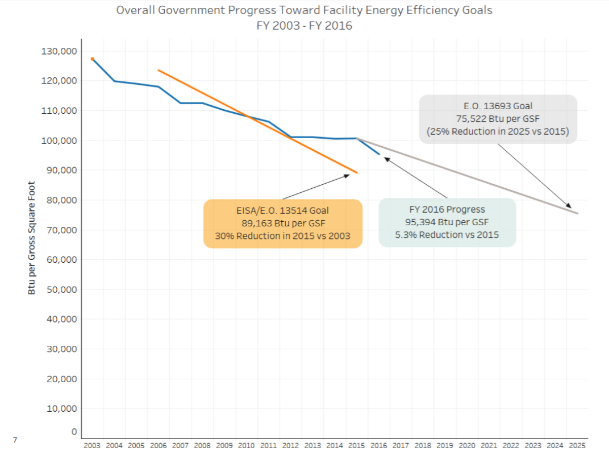

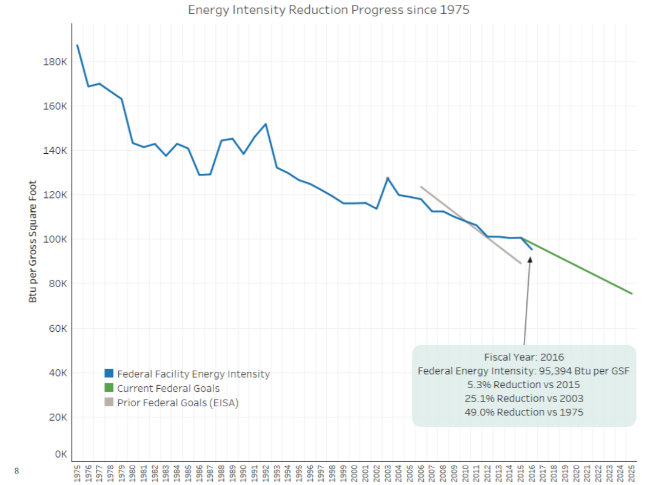

Though the United States has decreased the energy intensity of federal facilities by nearly 50 percent since 1975 (see Figure 1.), the federal government has missed opportunities to retrofit existing buildings. With increasingly tight budgets, agencies simply cannot afford to assign upfront appropriations away from existing priorities toward measures that would improve energy productivity, even if those investments would pay off quickly. Agencies today have more flexibility than ever to make energy investments with no upfront cost to taxpayers through energy savings performance contracts (ESPCs) and utility energy services contracts (UESCs), which were permanently authorized by the Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA) more than a decade ago. But here’s the thing: even though federal building managers have the option of using such contracts, most don’t. It’s a huge missed opportunity. But a push from lawmakers like the All-of-the-Above Federal Buildings Energy Conservation Act would change that.

Figure 1. Overall Government Progress Toward Facility Energy Efficiency Goals (FY 2003-FY 2016) and Energy Intensity Reduction Progress Since 1975. Note that the goals (identified by the gray and green bars in the graphs) as extended by E.O. 13693 have been revoked.

(Images source: DOE)

Often 15- to 20-years in duration, performance contracts must guarantee energy and water savings over the life of the contract, for a share of those savings—shifting the performance risk from the taxpayer to the private partner. ESPCs and UESCs allow agencies to achieve other priorities as well, including increased resilience, improved sustainability, better performance, and lower overall operations and maintenance expenses. It bears repeating, these public-private partnerships, or P3s, allow agencies to modernize the existing building stock at no upfront cost to the taxpayer. Over time, performance contracting has outperformed the promise, with federal partners realizing nearly twice the guaranteed savings once the contracts expire and full benefits accrue to the agencies.

This Bipartisan Congressional Bill Would Help

Removal of these barriers is the most important outcome driving the Alliance’s continued support for the All-of-the-Above Federal Building Energy Conservation Act, a bipartisan and bicameral bill re-introduced into the Senate by Sens. John Hoeven (R-N.D.) and Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) and introduced, for the first time, into the House of Representatives by Reps. Buddy Carter (R-Ga.) and Gene Green (D-Texas). The bill would require agencies to make all investments that are identified to be life-cycle cost-effective through energy audits of existing buildings while also removing a cost threshold for retrofits that currently serves as a disincentive to modernization.

By removing the barriers to investment represented by the fossil-fuel requirement and lack of timely upfront appropriations, and instead requiring cost-effective investment in energy-saving retrofits of existing federal buildings, the All-of-the-Above Federal Building Energy Conservation Act helps save taxpayer money while providing significant steps toward resilience and sustainability. Through performance contracting, agencies can modernize their buildings and save taxpayers money on energy costs. Together, it’s a win-win-win.

STAY EMPOWERED

Help the Alliance advocate for policies to use energy more efficiently – supporting job creation, reduced emissions, and lower costs. Contact your member of Congress.

Energy efficiency is smart, nonpartisan, and practical. So are we. Our strength comes from an unparalleled group of Alliance Associates working collaboratively under the Alliance umbrella to pave the way for energy efficiency gains.

The power of efficiency is in your hands. Supporting the Alliance means supporting a vision for using energy more productively to achieve economic growth, a cleaner environment, and greater energy security, affordability, and reliability.